By Ben Wheeler

For many, the name Martin Scorsese is synonymous with American cinema.

His films Raging Bull, Taxi Driver, and Goodfellas are considered by many to be among the greatest Hollywood has ever produced.

Others like After Hours and The King of Comedy have a distinctly cult following and have inspired art as varied The Weeknd’s 2020 album After Hours and Todd Phillip’s subversive 2019 take on the superhero genre Joker.

At the heart of almost all his movies is the character of the gangster.

When it was announced that his long-standing passion project Killers of The Flower Moon – an origin story for the Federal Bureau of Investigation that has just been nominated for 10 Oscars – had significantly shifted from a narrative that focused on the FBI to one that dwelled on and dealt with the Indigenous American perspective via the little-known history of the genocide of the Osage Nation, some feathers were ruffled.

Countless hours were spent in consultation with the Osage Nation and the tribe’s language experts, and Scorsese also met with Oklahoma’s Gray Horse community – partially descended from the scattered Osage victims – compelling the director to overhaul the whole script.

“After a certain point, I realized I was making a movie about all the white guys,” he said in an interview with Time. “Meaning I was taking the approach from the outside in, which concerned me.”

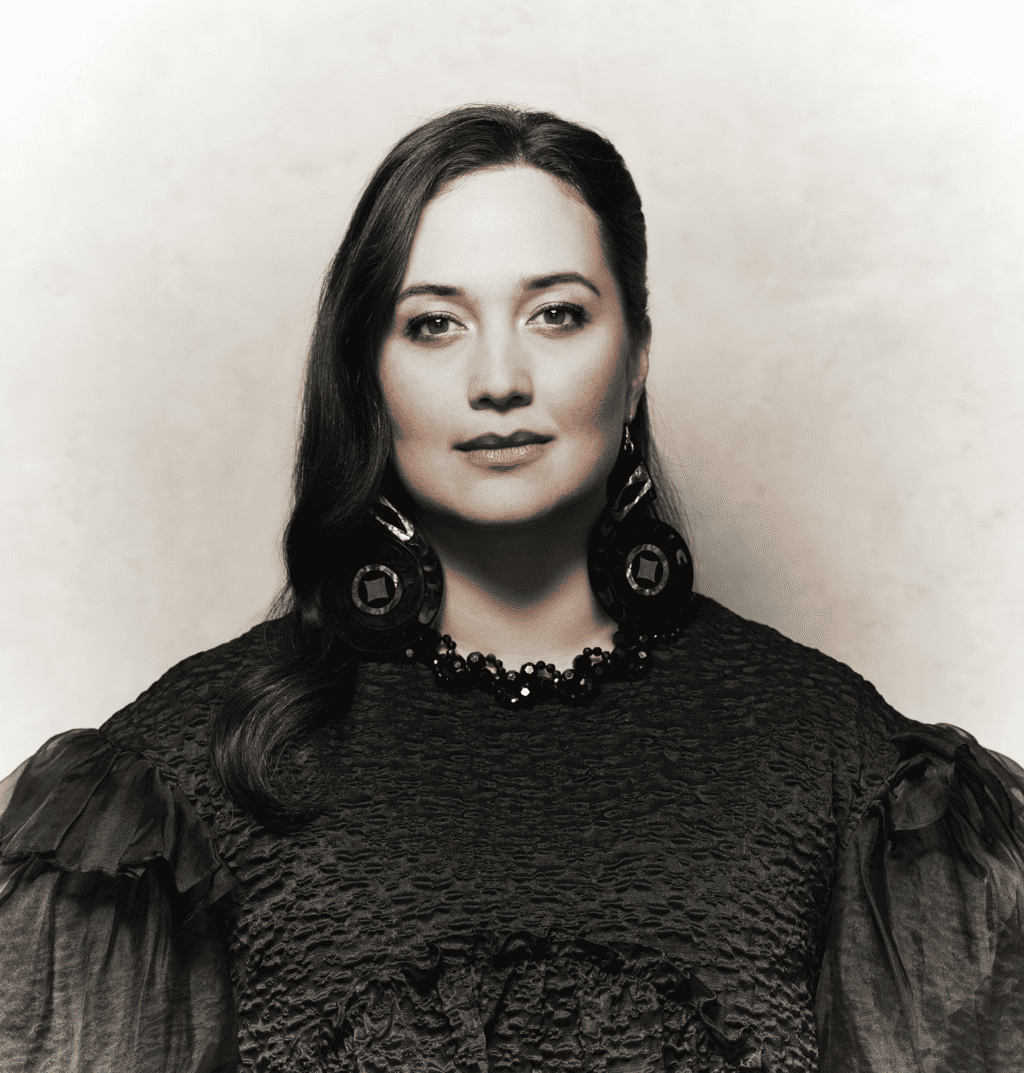

Now, thanks to these changes, Lily Gladstone has become the first Native American to be nominated for a Best Actress Oscar.

“It’s overdue, and it’s not the first,” she said in an interview with ABC News. “I remember how I felt when Keisha Castle-Hughes was nominated as the first Indigenous best actress in Whale Rider and seeing that film, seeing a young woman lead that kind of immense work and that kind of groundbreaking shift in the world, that was such an inspiration to me.”

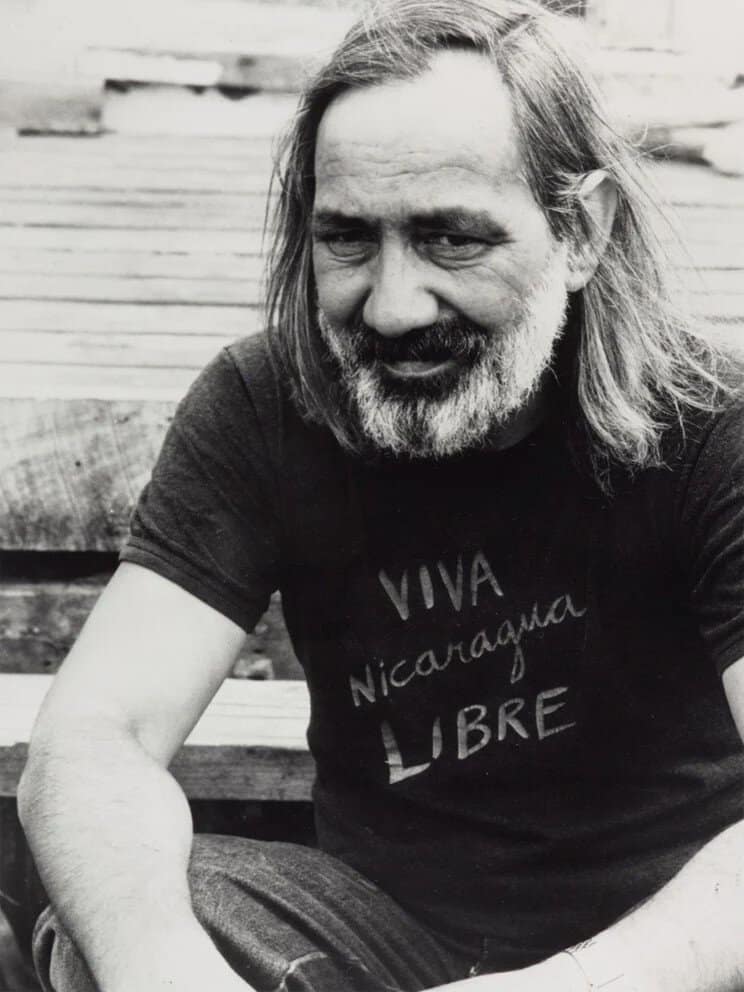

These attempts to remedy the imbalance in representation and perspective is reminiscent of the words of New Zealand filmmaker Barry Barclay, who described his work as not part of First Cinema — which came to represent the perspective of the Western invaders of Pacific cultures — but of Fourth Cinema, the camera on the shore.

His passionate advocacy for films to be made from an Indigenous Pacific perspective finds some correlation in the attempts Scorsese makes to allow Native Americans – almost always exoticised and the bearer of an oppressive cinematic gaze – to return a gaze that scrutinizes the colonizers of their country.

Killers of the Flower Moon opens with members of the Osage Indigenous American communities in 1919, dancing under a fountain of crude oil discovered beneath land over which, to some extent, they still had ownership rights. This leads to a montage of native faces costumed like they have just stepped out of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, and is immediately followed by their inevitable, violent murder at the hands of faceless colonial assassins.

“When this money started coming, we shoulda known it came with something else, cos it’s the white man’s money,” say an Osage Elder later in the film.

“They’re like buzzards circling our people. They’re gonna pick us body clean.”

I was reminded throughout, of the similar stories I have heard during my time in Fiji.

In the 1980s, for example, the Pacific nation of Nauru was described as the richest island in the world. A gross income upwards of $100 million a year from phosphate mining and a population of 4,000 meant that, according to one source, “most Nauruans don’t work, yet they have more than enough money to enjoy the comforts of modern society.”

“Overshadowing all of this good life,” it continues, “is the fact that the phosphate will run out in about ten years, and the flow of money will come to a sudden stop.”

And stop it did, with devastating results.

A further Oceanian counterpoint is found in the story of Banaba, destroyed and rendered uninhabitable by the British Empire and other phosphate mining interests.

The late, great Teresia Teaiwa’s poem mine land: an anthem (to the tune of “this land is my land”) is in fact part of a wider project she called “notes towards a treatment for a film project”.

In it, she says:

and though they gave us a bit of their money

they left us with other kinds of poverty

this land is mine land

it used to be our land

but now we’re living on the fiji islands

and though we’ve had our fair share of problems

our future’s full of possibilities

This sentiment – this note of optimism for the future – can be felt in the telling of a story long known by the indigenous population of a nation, but hidden in the shadows of dominant global narratives, obscured by the smoke and mirrors of the cinematic rewrites of colonial history.

And the potential source materials do not end there.

Here in Fiji, there are many stories that are in danger of being lost – tales that would make Scorsese’s hair curl into a buiniga.

Sairusi Nabogibogi, for example, described by the late Dr Brij V. Lal as “a charismatic criminal, a serial prison escapist, a proto-Fijian nationalist fiercely opposed to colonial rule, an admirer of Mahatma Gandhi and Kenneth Kaunda, a fiction writer of talent, a self-proclaimed messiah and divinely ordained saviour of his people.”

“This undoubted hero of the Fijian underworld of the 1950s and 60s,” laments Dr Lal, “survives only in the fading memories of a passing generation.”

There is also the story of Kunti, a female indentured labourer in Fiji who, on 10 April 1913, after alleged confrontational behaviour, was sent alone to an isolated banana patch at Nadewa in Rewa. Here, she was approached by one Overseer Cobcroft, who attempted to rape her. After fighting back and freeing herself from Cobcroft, Kunti ran to the Wainibosaki river and threw herself in despite being unable to swim.

It was only thanks to a young man by the name of Jagdeo, who was in a dinghy on the river, that she survived to tell her tale.

But this tale flew in the face of colonial narratives, especially those which identified the Indian female worker as the cause of all major social and moral ills of the plantation society.

The governments of India and Fiji conspired to quash, discredit, and dispel Kunti’s tale.

Its popularity in mass-circulating Indian newspapers, however, initiated powerful protests against the degradation of Indian women on colonial plantations. The resulting campaign, according to historian K. L. Gillion, garnered more support “than any other movement in modern Indian history, more even than the movement for independence.”

Despite belonging to a low, cobbler caste, Kunti was eulogised for her bravery, patience, and strength of mind.

Now, if these stories aren’t gangster, I don’t know what is.

Let’s not wait for the well-intentioned Scorsese’s of the world to adapt these tales. We may be waiting some time, when there is already a potent wave of film culture that has been growing across the Pacific for decades, and is finally reaching the shores of the Fiji Islands.

As Barry Barclay states, “Every culture has a right and responsibility to present its own culture to its own people. That responsibility is so fundamental it cannot be left in the hands of outsiders, nor usurped by them.”

The author is grateful to Dr Nicholas Halter, Senior Lecturer in History at the University of the South Pacific, and the writings of Dr Brij V. Lal and Barry Barclay.